Massacre

Between the 1970s and early 2000s, before the surge in queer visibility in Sydney, non-normative gender and sexual communities formed connections at hidden queer sites to navigate heteropatriarchal constraints. These sites, once vital hubs for queer life, became targets of violent acts, leading to 88 tragic murders. Utilising existing photographs, found in various LGBTQI+ publications and news sites, these drawings examine the series of ongoing artworks titled Massacre – Bodies That Matter, 2018/2026, spotlighting the violence faced by marginalised queers seeking acknowledgement, where societal condemnation and institutional neglect led to acts of violence. This inquiry contributes to understanding the historical and spatial dimensions of violence against LGBTQI+ individuals, calling for a rethink of modern drawing conventions to reveal the complexities of identity and sexuality.

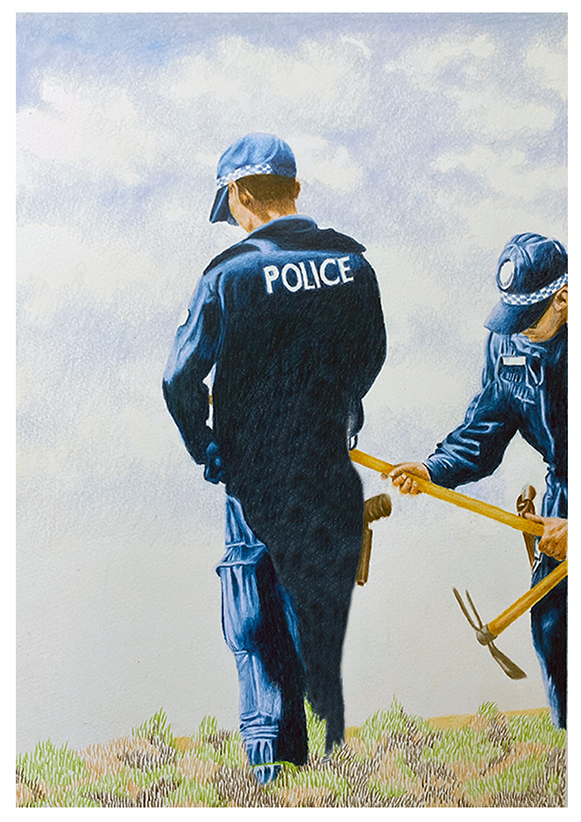

Glenn Walls. Massacre – Location of the murder of Scott Johnson on the 8th December, 1988, at Blue Fish Point in North Head near Manly, Sydney, Australia. The area was known as a gay beat.

Drawing on Paper. 297 x 420 mm. 2026

Glenn Walls. Massacre – Location of the murder of Scott Johnson on the 8th December, 1988, at Blue Fish Point in North Head near Manly, Sydney, Australia. The area was known as a gay beat.

Drawing on Paper. 297 x 420 mm. 2026

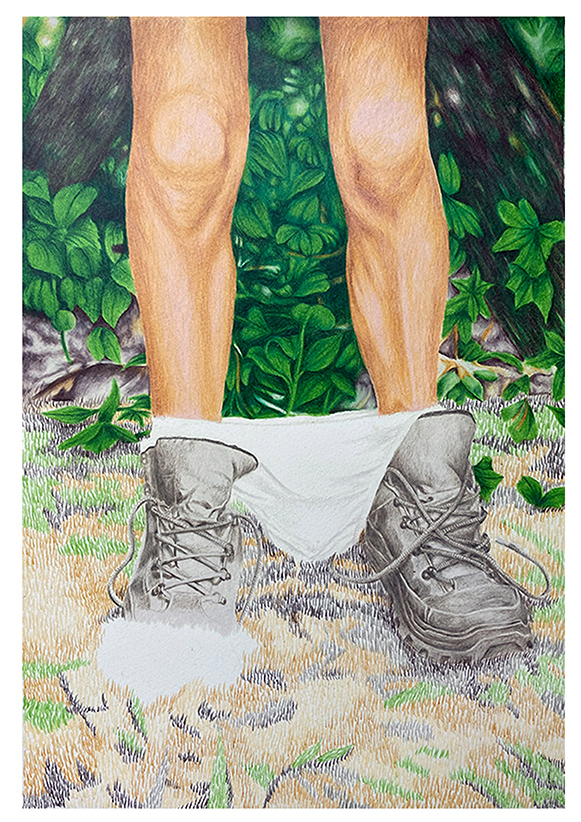

Glenn Walls. Massacre – According to journalist Greg Callaghan, “The Bondi Boys were a large group of 30 youths aged 12–18. They’re linked mainly to deaths at Marks Park and called themselves PTK (“People that Kill”) and PSK (“Park Side Killers”)”, (Callaghan, 2021) as carved in the drawing’s tree

Drawing on Paper. 297 x 420 mm. 2026

Glenn Walls. Massacre – “It was December 10, 1988, when Scott’s naked body was found by two rock fishermen at the base of the cliff, near Blue Fish Point, just south of Manly, on Sydney’s northern beaches. Police immediately deemed the death a suicide. Furthermore, as Scott’s clothes had been found neatly folded on the clifftop above, the death was considered a “ritual suicide” (Kontominas, 2017).

Drawing on Paper. 297 x 420 mm. 2026

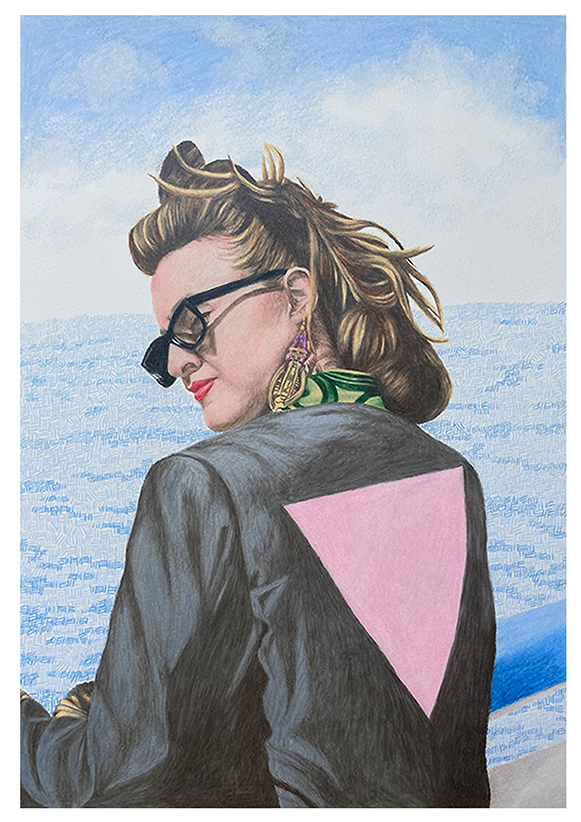

Glenn Walls. Massacre: Madonna, a leading advocate for the LGBTQI+ community, was at her height when these hate crimes were taking place in Sydney.

Drawing on Paper. 297 x 420 mm. 2026

Glenn Walls. Massacre – “Marks Park, a grassy verge capping the headland and the concrete pathway skirting the cliff face, had been a gay beat – a place where homosexual men would socialise and hook up – since at least the late 1920s” (Callaghan, 2021)..

Drawing on Paper. 297 x 420 mm. 2026 (Incomplete)

References

Callaghan, G. (2021, October 1). ‘A willingness to write crimes off’: on the trail of the Bondi killers. The Age. https://www.theage.com.au/national/a-willingness-to-write-crimes-off-on-the-trail-of-the-bondi-killers-20210903-p58oo4.html

Davis, K. (2007). Bondi’s underbelly: the ‘gay gang murders’. QUEER SPACE: CENTRES AND PERIPHERIES, UTS. file:///Users/gfinley/Downloads/Bondis_underbelly_the_gay_gang_murders.pdf

Kontominas, B. (2017, November 30). Scott Johnson: Inside one brother’s 30-year fight to find the truth. ABC News Australia. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-11-30/scott-johnson-inside-brothers-fight-to-find-the-truth/9211466

Massacre – Bodies the Matter: the mapping of queer violence in Sydney, Australia between 1970 and 2010

Published November 2024. Taylor & Francis. International Journal of Cartography.

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/23729333.2024.2419692

ABSTRACT

Between the 1970s and early 2000s, before queer visibility came to the fore in Sydney, many people living under heteropatriarchy developed ways to interact at queer sites. Unintelligible to the mainstream cultural imagination, the connections enabled by these sites allowed queer life to flourish. However, when they became known to other social groups the sites became epicentres of catastrophic violence, linked to 88 murders. Drawing on Vinicius Almeida’s (2022) concept of queer cartography, this article discusses an ongoing series of artworks titled Massacre – Bodies That Matter that challenges the heteronormativity embedded in urban space and highlights the violence inflicted on a marginalised group who during this period were fighting for their human right of recognition. Aided by religious organisations and institutions that denounced queer life as unacceptable to mainstream society, a collective of individuals and gangs took it upon themselves to rid society of this supposed abhorrent scrouge. In identifying forgotten queer spaces, mapping can explore the intersection of queer identity and violence. The article and artworks argue for the legitimacy of queer life, addressing the extent of violence perpetrated against the LGBTQI+ community in Sydney in the period discussed. This contributes to a more comprehensive understanding of the historical and spatial dimensions of violence against the LGBTQI+ community, which extends to a consideration of the reductive aesthetic language of modernist maps obscure a problematic relationship to identity and sexuality.

“Our blood runs in the streets and in the parks and in casualty and in the morgue

Our own blood, the blood of our brothers and sisters, has been spilt too often …

Our blood runs because in this country our political, educational, legal and religious systems actively encourage violence against us …”

- One in Seven Manifesto, Sydney Star Observer, April 5, 1991 (Sydney Star Observer, 1991).

Keywords

LGBTQI+ visibility, queer violence, queer cartography, Sydney queer hate crimes.

Link to the full research paper below.

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/23729333.2024.2419692

Glenn Walls. Massacre (after Felix). Digital Print on 4 × A3 paper stacks. 2018/2024.

Cite this paper.

Walls, G. (2024). Massacre – Bodies the Matter: the mapping of queer violence in Sydney, Australia between 1970 and 2010. International Journal of Cartography, 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/23729333.2024.2419692

My life (The Failure of Modernism)

Glenn Walls. Untitled (Fierce bitch seeks future ex-husband, David McDiarmid). 2024. Bauhaus coffee mug, dollar notes, printed paper. Various dimensions.

Fierce bitch seeks future ex-husband is an artwork by David McDiarmid created in 1994.

Glenn Walls. Untitled (Choose Life, Herbert Bayer). 2024. Bauhaus coffee mug, dollar notes, printed paper. Various dimensions.

Glenn Walls. Untitled (Less is a bore. Consume more, Herbert Bayer). 2024. Bauhaus coffee mug, dollar notes, printed paper. Various dimensions. Less is More is a quote from German architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe.

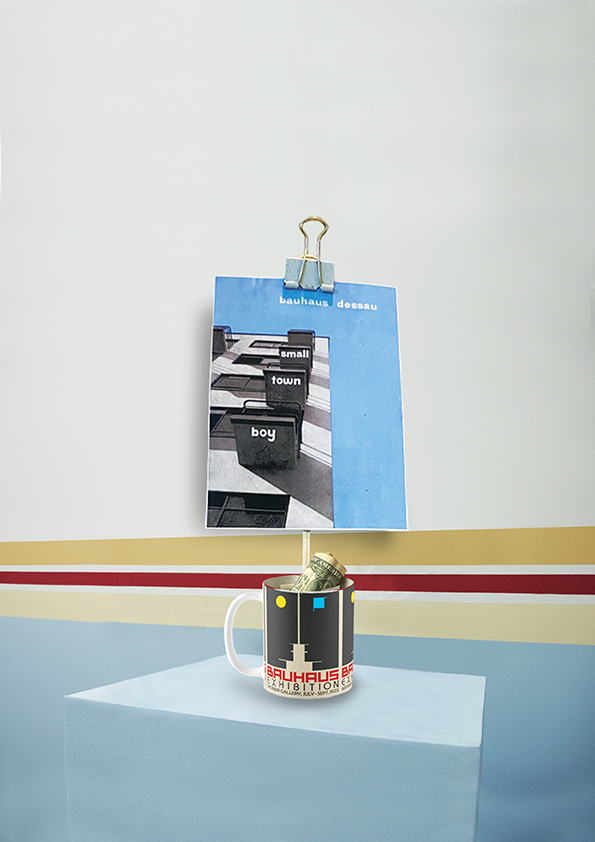

Glenn Walls. Untitled (Smalltown Boy, Herbert Bayer). 2024. Bauhaus coffee mug, dollar notes, printed paper. Various dimensions.

Smalltown Boy is a song by Bronski Beat released in 1984.

Glenn Walls. Untitled (Smalltown Boy, Herbert Bayer). 2024. Bauhaus coffee mug, dollar notes, printed paper. Various dimensions.

Smalltown Boy is a song by Bronski Beat released in 1984.

In the Park

Glenn Walls. (Death and Dancing) In the Park. 2024. Alvar Aalto, Stool 60, 1933, Gay flag, Stencil, Yellow Paint. Contains an image of the painting, “Two dancing male figures in a landscape”. Anonymous, French, 18th Century. The Met Fifth Avenue. Installation view.

Glenn Walls. (Death and Dancing) In the Park. 2024. White paper stack, Yellow Paint. Contains an image of Ross Warren who was one of the victims of the gay killing spree that took place in Sydney in the late 20th Century. Ross Warren is suspected of being murdered on 22nd July 1989.

Glenn Walls. (Death and Dancing) In the Park. 2024. Alvar Aalto, Stool 60, 1933, Gay flag, Stencil, Yellow Paint. Contains an image of the painting, “Two dancing male figures in a landscape”. Anonymous, French, 18th Century. The Met Fifth Avenue. Installation view. Also contains an image of Ross Warren who was murdered in 1989.

Glenn Walls. (Death and Dancing) In the Park. 2024. Alvar Aalto, Stool 60, 1933, Contains an image of Scott Johnson who was murdered on the 8th December 1988 in Manly.

Glenn Walls. (Death and Dancing) In the Park. 2024. Alvar Aalto, Stool 60, 1933, Gay flag, Stencil. Contains an image of the painting, “Two dancing male figures in a landscape”. Anonymous, French, 18th Century. The Met Fifth Avenue. Installation view.

Artist Statement

Between the 1970s and early 2000s, before queer visibility came to the fore in Sydney, Australia, many gender and sexual non-normative people living under the conditions of heteropatriarchy managed to develop different ways of interacting with others at queer sites and spaces. Unintelligible in the mainstream cultural imagination, these practices of communication and connection were a means of survival that enabled queer life to flourish. However, when the location of these queer sites became known to certain other social groups, they became epicentres of catastrophic violence, linked to 88 murders. The works developed for “In the Park” explore how gender and non-normative people gravitated to Sydney to create new identities and communities making them the target of stigmatization and violence by a small minority. The artworks argue for the legitimacy of queer life, revealing the extent of violence perpetrated against the LGBTQI+ community. I hope to contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of the historical and spatial dimensions of violence against the LGBTQI+ community and advocate for its more nuanced portrayal in contemporary narratives. By harnessing the language of modernist furniture and maps which created a sense of clean, clinical space free of interpretation, these artworks contest dominant views of modernist design and humanise modernist/minimalist theory and practice to obscure its problematic relationship to identity and sexuality.

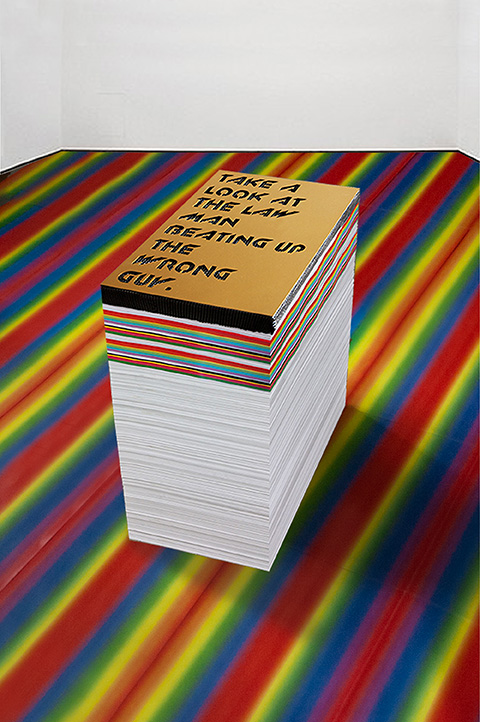

Forever Young. Installation view.

Glenn Walls. Untitled (Take a look at the law man beating up the wrong guy). Metal plate, paper stack. 2022. Words are taken from David Bowie’s 1971 – 73 song “Life on Mars”.

Comments Off on Forever Young. Installation view.

THE AUSTRALIAN UGLINESS

Glenn Walls. Cover of Robin Boyd’s book ‘The Australian Ugliness’. First published in 1960.

Original cover drawing by Robin Boyd. Reimagined in 2023.

Glenn Walls. Super rainbow. Mirror tiles, neon light, skate wheels and mirror plinth. 2023

Glenn Walls. Super rainbow. Mirror tiles, neon light and skate wheels. 2023. Based on the Italian architectural

group, Superstudio’s work, The Continuous Monument: An Architectural Model for Total Urbanisation. 1969 – 71.

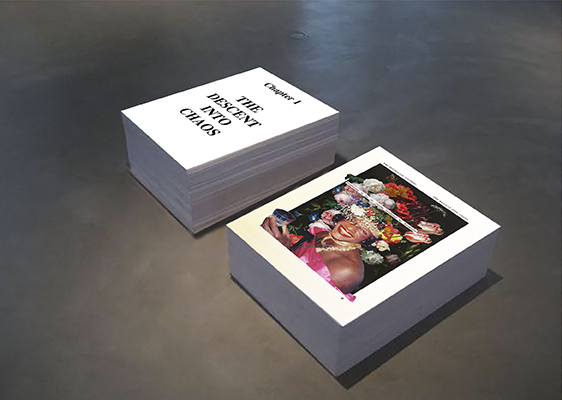

Glenn Walls. Robin Boyd, The Australian Ugliness. Chapter 1: The Descent into Chaos. Published in 1960.

The first chapter of Robin Boyd’s 1960 book, The Australian Ugliness. Paper. 2023

Glenn Walls. Robin Boyd, The Australian Ugliness. Chapter 1: The Descent into Chaos. Pg 7. Published in 1960.

Pink eyes stare out for the first glimpse of Australia still filled with an even, empty greyness. Digitally altered. Paper. 2023.

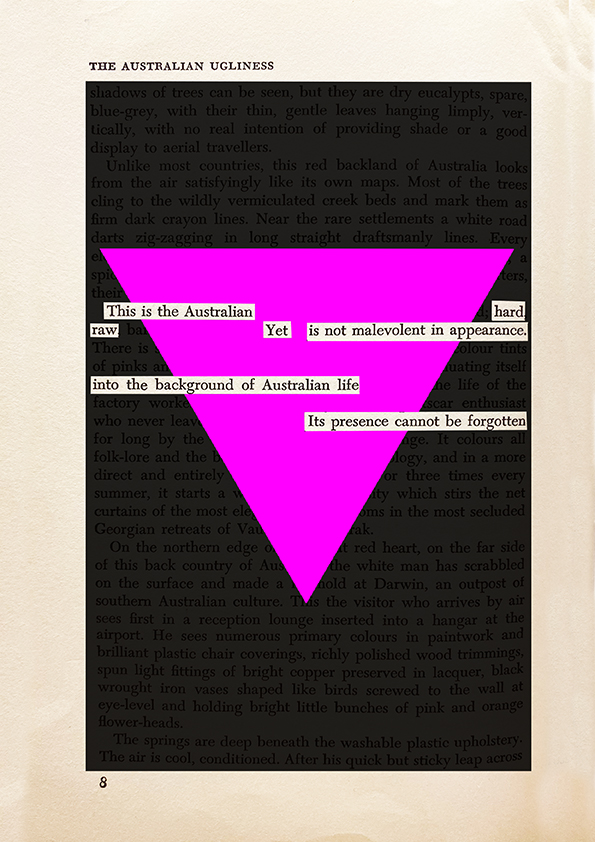

Glenn Walls. Robin Boyd, The Australian Ugliness. Chapter 1: The Descent into Chaos. Pg 8. Published in 1960.

This is the Australian, hard, raw, yet is not malevolent in appearance into the background of Australian life. Its presence cannot be forgotten. Digitally altered. Paper. 2023.

Glenn Walls. Robin Boyd, The Australian Ugliness. Chapter 1: The Descent into Chaos. Pg 9. Published in 1960.

Featurism is by no means confined to Australia. Digitally altered. Paper. 2023.

Glenn Walls. Robin Boyd, The Australian Ugliness. Chapter 1: The Descent into Chaos. Pg 9. Published in 1960.

Featurism is by no means confined to Australia. Paper stacks, A3 in size. Installation view. 2023.

Glenn Walls. Robin Boyd, The Australian Ugliness. Chapter 1: The Descent into Chaos. Pg 10. Published in 1960.

“To hide the truth and camouflage. Camouflage has always been a favoured practice. In Australia. A faint stigma. Veneering has become entirely respectable. Digitally altered. Paper. 2023.

Glenn Walls. Robin Boyd, The Australian Ugliness. Chapter 1: The Descent into Chaos. Pg 11. Published in 1960.

Quotes are taken from ‘Queering the Map’ located in Melbourne. Names and ages are fictional. Digitally altered. Paper. 2023.

https://www.queeringthemap.com/

Glenn Walls. Super rainbow. Mirror tiles, neon light and skate wheels. 2023. Based on the Italian architectural

group, Superstudio’s work, The Continuous Monument: An Architectural Model for Total Urbanisation. 1969 – 71.

Robin Boyd, The Australian Ugliness. Published in 1960.

The Australian Ugliness by Glenn Walls.

Australian architect and architectural critic Robin Boyd’s seminal critique on Australian suburban life and architecture The Australian Ugliness was first published in 1960. In the book, Boyd highlighted Australian architecture’s need to mask its true identity with kitsch materials and imported architectural styles unsuited to the Australian climate and landscape. Boyd referred to this phenomenon as “featurism”. As Emma Letizia Jones states:

“Boyd rejected outright the pervasive signs of a commercial kitsch architectural currency he labelled “Featurism”, and it was characterised by veneers of all sorts: brick veneer construction in the suburbs, brightly coloured plastic veneers in the home, veneers of advertising in the streets, veneers of “Australian character” on an international Western culture. Against this imported Featurism worn as a prettifying mask, Boyd argued for a truly Australian Modern beyond mere cosmetic effects, which he sought through his own architectural projects” (Jones 2014)

Featurism provided architects and builders the opportunity to ‘cover up’ the true identity of a building making it appear as something it was not.

Robin Boyd, The Australian Ugliness. Contents page. Published in 1960.

But this was a period when masking was all the rage, not just in architecture. As Emma Letizia Jones also states, “Featurism in short was the adopted visual style of an ambivalent, uncertain population at odds with its surroundings, unsure of how to inhabit them, clinging to the edges of a continent and looking everywhere for answers but into its own interior” (Jones 2014 p. 96). The post-war era of the 1950s and 1960s was a period of extreme conservatism in Australia. This period coincided with conservative social and cultural attitudes to sexuality and identity. To survive many LGBTQI+ people felt the need to mask their identity. Rachel Morgain highlights the repression and victimisation during this period. She states:

“The years following the Second World War saw a drive to consolidate the family, encourage women to have children and push them out of unconventional war-time jobs, so that there would be positions for returned soldiers. The campaign against homosexuality in the 1950s was an escalation of this process, seeking to rectify the decline in social discipline that conservatives argued had occurred during the war. Over a few years, there was a sharp increase in the number of people charged with and convicted of homosexual offences. Police actively entrapped homosexual men. A special squad targeting homosexuality was set up in the Victorian police and the NSW police superintendent labelled homosexuality ‘the greatest social menace facing Australia’. Homosexuals in the public service became particular targets. There were moves to isolate homosexual men in NSW prisons and to have them locked up in mental institutions. The tabloid press was filled with scandals about gay men. What little coverage there was in the quality press sent a clear message to anyone thinking of straying from the heterosexual norm: that path could lead only to shame and arrest”. (Morgain 2004 p. 5)

Robin Boyd, The Australian Ugliness. Chapter 1: The Descent into Chaos. Pg 7. Published in 1960.

To survive during this period masking by the LGBTQI+ community became a necessity. Certain clothing, hairstyles, and jewellery were to be avoided. Appropriate clothing provided the armour that concealed one’s true identity. Joel Sanders highlights this in the preface to the 2021 reissue of his 1996 book ‘Stud: The Architecture of Masculinity’, “I came to realize that the clothing that clad bodies behaved like the cladding of buildings: wall finishes, paint, fabrics, curtains, upholstery and furniture are like garments, culturally coded applied surfaces that designers use to fashion human identity” (Sanders 2020 p. 8). Similarly, Boyd’s ‘featurism’ that aimed to clad a building in an identity that, according to him was fake, became locations where queer life happened. In this project, I argue that despite the masking of both queer people and architecture, queer identity occurred allowing architecture to become queer space via memory.

By the 1960s bold civil liberties groups and the New York Stonewall Riots in 1969 were seen as a turning point, gay liberation and activism exploded. The LGBTQI+ community began to move out of the fringes and into the mainstream. As laws were repealed, homosexuality decimalised, and attitudes changed our relationship to queer identity and queer space also changed. Boyd’s book The Australian Ugliness provided a snapshot of a particular time in Australia’s cultural and built history, one that was masked in Featurism in search of an identity. But as Peter Conrad states: “Books that quarrel with the way things inevitably lose their point when things change. But it’s no disgrace to re-treat into history, and The Australian Ugliness testifies to a confused and uncertain period in the national life that, with a little help from Boyd, we happily outgrew” (Conrad, p. 63). Sadly, masking one’s identity is still an issue for many in the LGBTQI+ community. To suggest all is well regarding LGBTQI+ rights is an understatement1. However, this project provides the opportunity to engage with queer lives and queer space by marking the location within the pages of Boyd’s book where queer memories occurred and are remembered.

Robin Boyd, The Australian Ugliness. Chapter 1: The Descent into Chaos. Pg 8 & 9. Published in 1960.

Regardless of the featurism found in Australian suburban homes, they were still locations where memories were made. Inspired by artist Tom Phillips’s project ‘A Humument; A Treated Victorian Novel 1966 – 2016, in which Phillips randomly ‘began to doctor the pages with images, both abstract and figurative’ (Kidd, 2012), this project uses the locations found in the text of Boyd book The Australian Ugliness as data points to highlight queer spaces that had the potential for this to occur through fictional recollections, photographs, digital imagery and drawings placed on Boyd text. These are fictional coming-out stories of opportunities that were never recorded but may have happened, but because of the entrenched homophobia and laws in place during this period, a veneer was put in place to mask queer existence in the built environment. With that veneer removed we are now able to engage with locations marked as a place that ‘queer’ happened and remember.

Notes.

1. In the United States of America there have been over 120 Bills Restricting LGBTQ Rights Introduced Nationwide in 2023. Most relate to trans issues. https://www.tracktranslegislation.com/

Bibliography

ABC News 2015, Timeline: 22 years between first and last Australian states decriminalising male homosexuality, ABC News website, accessed 2 February 2023. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2015-08-24/timeline:-australian-states-decriminalise-male-homosexuality/6719702

Australian Human Rights Commission 2023, Face the facts: Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex People, Australian Human Rights Commission website, accessed 2 February 2023. https://humanrights.gov.au/our-work/education/face-facts-lesbian-gay-bisexual-trans-and-intersex-people

Bleakley, P 2021, ‘Fish in a Barrel: Police Targeting of Brisbane’s Ephemeral Gay Spaces in the Pre-Decriminalization Era’, Journal of homosexuality, vol. 68, no. 6, Routledge, United States, pp. 1037–1058.

Boyd, R. (1960). The Australian ugliness. F. W. Cheshire, Melbourne.

Burke, S 2018, Find Yourself in the Queer Version of Google Maps, VICE website, accessed 30 January 2023.

https://www.vice.com/en/article/ne9kjx/queering-the-map-google-maps-lgtbq

Carlson, D 2012, The education of eros: a history of education and the problem of adolescent sexuality, Routledge, New York.

Conrad, P 2009, ‘Coming of Age: Peter Conrad on Robin Boyd’s “The Australian Ugliness” Fifty Years On’, Monthly (Melbourne, Vic.), no. Dec 2009 – Jan 2010, Schwartz Publishing Pty. Ltd, Melbourne, Vic, pp. 60–63.

https://search.informit.org/doi/epdf/10.3316/informit.655309633983791

Dahmubed, C 2018, ‘Memorializing queer space’, Crit, no. 83, pp. 71-78.

Jones, EL 2014, ‘Rediscovering “The Australian Ugliness”. Robin Boyd and the Search for the Australian Modern’, Studii de istoria și teoria arhitecturii, vol. 2014, no. 2, Ion Mincu University of Architecture and Urbanism, pp. 94–114. https://sita.uauim.ro/article/2-jones-rediscovering-the-australian-ugliness

Kidd, J 2012, Every Day of my Life is Like a Page.The Literary Review, Issue 400.Tom Phillips. Accessed 15 February 2023.

https://www.tomphillips.co.uk/humument/essays/item/5858-every-day-of-my-life-is-like-a-page-by-james-kidd

Kontominas, B 2017. ‘Scott Johnson: Inside one brother’s 30-year fight to find the truth’. The Age. Accessed 14 February 2023.

https://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-11-30/scott-johnson-inside-brothers-fight-to-find-the-truth/9211466

LGBTQI+ Health Australia 2021, Snapshot of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention Statistics for LGBTIQ+ People, LGBTQI+ Health Australia website, accessed 2 February 2023. https://www.lgbtiqhealth.org.au/statistics

London Transport Museum 2023, Mapping London: the iconic Tube map. London Transport Museum website, accessed 1 February 2023. https://www.ltmuseum.co.uk/collections/stories/design/mapping-london-iconic-tube-map

Morgain, R. 2004. Sexual liberation: fighting lesbian and gay oppression. Australian National University Publications

https://openresearch-repository.anu.edu.au/handle/1885/42704

National Geographic 2023, Map, National Geographic website, accessed 2 February 2023. https://education.nationalgeographic.org/resource/map

Oswin, N. (2008) ‘Critical geographies and the uses of sexuality: deconstructing queer space’, Progress in Human Geography, 32(1), pp. 89–103. doi:10.1177/0309132507085213.

Queering the Map. 2023. Queering the Map. https://www.queeringthemap.com/

Sanders, J 2020 (Reissue), Stud: Architectures of Masculinity, Taylor & Francis Group, Milton.

SBS 2016, The history and importance of gay beats, SBS website, accessed 6 February 2023. https://www.sbs.com.au/topics/pride/agenda/article/2016/10/17/history-and-importance-gay-beats

Strike Force Parrabell 2018, New South Wales Police Force. viewed November 11 2022, https://www.police.nsw.gov.au/safety_and_prevention/your_community/working_with_lgbtqia/lgbtqia_accordian/strike_force_parrabell

Wotherspoon, G 2017, Gay Hate Crimes in New South Wales from the 1970s, viewed 11th November 2022, https://www.acon.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/In-Pursuit-of-Truth-and-Justice-Report-FINAL-220518.pdf.

Forever Young

Violence against LGBTQI people continues with the recent shooting inside and outside a gay nightclub in Oslo, Norway in the early hours of Saturday 25th June 2022

Glenn Walls. Untitled (Take a look at the law man beating up the wrong guy). Metal plate, paper stack. 2022. Words are taken from David Bowie’s 1971 – 73 song “Life on Mars”.

Glenn Walls. Untitled (Forever Young. Marsha P. Johnson). Digital print. 2022. Words are taken from the 1984 Alphaville song “Forever Young”.

Forever Young is a continuation of the series “Massacre – Bodies that Matter” from 2018 – 2019.

Violence against LGBTQI people continues with the recent shooting inside and outside a gay nightclub in Oslo, Norway in the early hours of Saturday 25th June 2022.

More works to follow.

https://www.abc.net.au/news/2022-06-25/norway-nightclub-shooting-police-possible-terrorism/101183546

leave a comment